Three Days After / In Conversation with Karen Haber

by J.T. Dockery

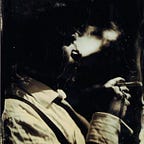

The illustration above represents my approach to a visualization of Karen Haber’s “Three Days After,” inspired not just by aclose reading of her story but also influenced by correspondence with that story’s author, who graciously agreed to discuss her work.

I. Context // Preamble:

Karen Haber is the author of several novels, including Star Trek Voyager: Bless the Beasts and editor of the Hugo-nominated Meditations on Middle-Earth: New Writing on the Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien (including work by Orson Scott Card, Ursula K. Le Guin, Raymond E. Feist, Terry Pratchett, Charles de Lint, George R. R. Martin & more). “Three Days After,” first published in the 2014 collection of her short fiction, The Sweet Taste of Regret, was subsequently anthologized in the Robert Silverberg-edited anthology, This Way to the End Times: Classic Tales of the Apocalypse.

I first encountered “Three Days After” in the pages of that anthology in a class taught by Dr. Anne Gossage at Eastern Kentucky University. Gossage began teaching Science Fiction as literature at Penn State, the first institution in the United States to consistently/continually instruct the genre in an academic context. She carried the torch of that innovation as standard practice as she continued on/continues to teach the genre as literature at EKU.

With most classes fully online, a few courses were still meeting in person in a time of global pandemic in the winter of 2020. In this case study, a classroom distanced socially and wearing our masks: an appropriate (or at least “appropriate”) time to be studying a collection of apocalyptic short fiction.

My response to Haber’s story then as now is that it invites interpretation, perhaps a multiplicity of possible meanings. Dr. Gossage pointed out that the main character’s name is “Phelia,” which could be interpreted as short for/an allusion to Ophelia, as in Shakespeare/Hamlet. I had not caught that allusion during my initial reading and was surprised to have missed it, as in hindsight it seemed blatant (more on that, later).

The ambiguity and multiple possibilities inspired in some students an uncomfortable distance between themselves and their experience of the story, but the enigma (or enigmas, plural) of its construction caused me to “lean in” to the carefully constructed prose. When given the opportunity to write about it for the class, I selected “Three Days After” as subject for further scrutiny.

After writing the essay on the story, I continued to ponder the nuance/artistry/craft of Haber’s prose. In the continuing reverberations of reflection, a lightbulb popped, and I sought out Ms. Haber herself, sending to her an email of introduction. She replied to that email and agreed to engage in conversation on the subject of her story.

I made the resultant-of-the-class essay available: here. I do not offer this essay as artifact of monumental academic achievement, rather it is what was accomplished as a fulfillment of assignment for the course by the deadline, with no further revision. I make this essay available, as Haber requested to read it as she waited for mmy questions, so the essay shared between us served as a preface to and/or a context for our/the following discussion.

II. Conversation w/ Haber:

Karen Haber: I thoroughly enjoyed reading your essay on “Three Days After.” You made a lot of pertinent observations. I’m especially happy to see that you noticed my reference to Seurat and drew the connection to my impressionistic handling of the story. Although I did not consciously select Phelia’s name to echo Ophelia from Hamlet, that’s a nice guess and would have added another layer of meaning not out of place with the effect I was working towards.

In writing the story I was aiming for impressionistic handling of varying realities and science fictional tropes while indulging in some mordant observations of early 21st century American culture and the workplace. I’m flattered that you have spent so much time on my story, and glad that it intrigued you to such an extent.

J.T. Dockery: If it does not diminish the story in your estimation, would you apply labels to the “tropes” and “observations” that you mentioned before as flowing into what would become the story? Which sparks a second, sub-question: what do you think the process or processes of writing the story may have altered regarding what you were initially/consciously intending to accomplish with it?

Haber: I was interested in working within the tradition of end-of-the-world stories (i.e. “Vintage Season” by C.L. Moore and Henry Kuttner under the penname Lawrence O’Donnell).

I don’t think the process of writing the story altered my intentions very much. Certain possibilities or ideas develop, of course, as one writes, but it’s important to know where you’re going.

Dockery: Rather than seeking a “solution” to the mystery, I read the story as a fragmented portrait of a fragmented individual and accepted that on the surface as the point, even the meaning or theme of the story. I am wondering as the author if you considered that your intent?

Haber: I didn’t really have an agenda for how the story would be read. The fragmented portrait is one interpretation that I think is valid. Alternative realities is another.

Dockery: We discussed previously the reference to Seurat. However, the actual line in the story, referring to the “hisses” and “blizzard of scales” from Phelia’s television is: “Jackson Pollock channeling Seraut.” Was the Seurat/Pollock line for you at all a “throw-away” bit of vivid prose or do you consider it as definitive to the story as I do as reader? And that question leads me asking if you would mind discussing how you might perceive visual art and artists may (or may not) influencing your approach to writing fiction, in “Three Days After,” or otherwise?

Haber: I wouldn’t call it a “throw-away,” but I would not give that line much more weight than it already has. Visual art occasionally may give me an idea for a story, although not in this case. When I was writing novels, I would keep a tear-sheet file of interesting/inspirational images, both photographic and other media.

Dockery: When you intimated that you were trying to tell an “impressionistic” story, I wonder if that — multiple versions of the same subject, more akin to what a visual artist might do with a theme — is something along the lines of what you were thinking about/creating in prose?

Haber: That’s probably true. I didn’t think of it at the time, but it seems apt. I like your notion, mentioned in one of your longer questions, of a portrait of Phelia interpreted by Richard Powers channeling Millais’s Ophelia. I think that the writer must have a strong visual image to support the story she is telling.

[I provided for Haber in an email containing the “long versions” of my questions, to provide for her more of the thinking behind my questions but optional for her to read. It was this that she references here, the notion of Phelia by Powers referencing Millais’s Ophelia is what the illustration at top represents…if not the imagined Richard Powers version, then my version of that imagined/imaginary notion.]

Dockery: Thank you so much for your time and for having written a story that captured my imagination. While the processes of closely scrutinizing “Three Days After” have been rewarding, surprising, even illuminating, I can’t help but feel that perhaps I’ve looked too far for too long under the hood of it, too closely in the mouth of the story as gift horse, proverbial (if you’ll forgive my mixing of metaphoric cliches, meant with a tone of humor). I look forward to reverting to a more fundamental state of original beguilement with and by the story. Finally, I’d love to ask you just what is “THE SOUND,” but I am comfortable in both knowing and not knowing or knowing that even in knowing, it/”THE SOUND”/knowing changes. For me as reader, that is the story of “Three Days After.”

Haber: THE SOUND is mutable, and rather than explain it I think I’ll just leave it to your excellent imagination.